Tech consultant/journalist Patrick Kennedy says that some of the claims made in a Bloomberg reports about alleged spy chips in servers used by Apple, Amazon, and other tech firms are completely implausible and that others are “impossible.”

Writing for STH, Kennedy opens by addressing the “astounding plausibility and feasibility gaps in Bloomberg’s description of how the hack worked.”

Today we are going to more thoroughly address the Bloomberg Businessweek article alleging that China targeted 30 companies by inserting chips in the manufacturing process of Supermicro servers. Despite denials from named companies and the technology press casting some reasonable doubt on the story, Bloomberg doubled down and posted a follow-up article claiming a different hack took place. In this piece, we are going to present a critical view of Bloomberg’s claims, as supported by anonymous sources, in order to allow our readers to decide for themselves the credibility of Bloomberg’s reporting in this case.

Kennedy says the the whole principle of how the spy chip thing worked is nonsensical. The publication claims the Baseboard Management Controller (BMC) was key to the hack. The chip is operational, even when a server has been turned off or has crashed. The story claims the BMC was able to download code via the internet. Kennedy says this is unlikely in a company of any size, much less one the size of Amazon or Apple.

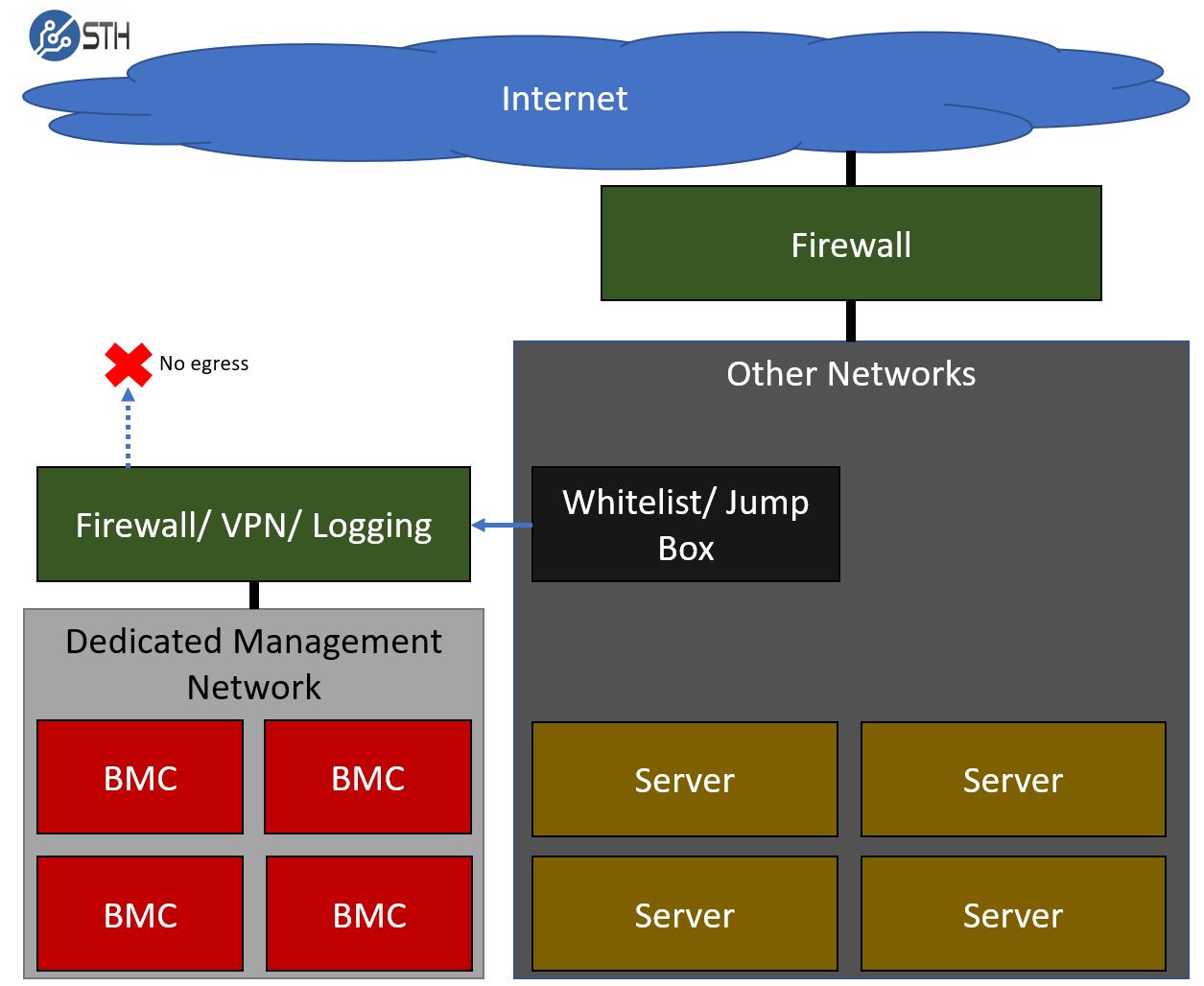

If you have an unsophisticated network or a lack of understanding about the topic, you may think that this is how BMC’s are networked.

Standard industry practice guards against this attack vector.

Even smaller organizations with a handful of servers generally have segregated BMC networks. That basic starting point, from where large companies take further steps, looks something like this:

Kennedy continues that Bloomberg’s claim that the BMC has access to code running on servers even when they’re turned off is “patently false.”

That is not how this technology works […] When the BMC is powered on, hard drives, solid state drives, the server’s CPU (for decrypting data) and memory are not turned on […] When a server is powered off it is not possible to access a server’s “most sensitive code.” OS boot devices are powered off. Local storage is powered off for the main server. Further encrypted sensitive code pushed from network storage is not accessible, and a BMC would not authenticate.

Kennedy says the ideas of a BMC injecting code into the CPU is physically impossible.

The hardware implanted does not have the pin count nor the processing power to perform this interception […] Note that RAM to CPU communication happens over thousands of pins. Each CPU has 2011 pins for communicating with the rest of the server. RAM pins take up several thousand of these channels […]

This communication also happens at relatively high clock speeds, so keeping up with the bandwidth is a challenge for even CPU designers. There is no way for a small chip to attack the “temporary memory” (RAM) to CPU communication.

Kennedy goes on to detail how complicated it would be for a so-called “spy chip” to carry out the processes in Bloomberg’s claims. The article goes into heavy detail, more than we can cover here, and is recommended reading for individuals interested in the spy chip situation.

Kennedy closes his article by joining those calling for a retraction of the Bloomberg article.

There is now enough evidence pointing to systematic discrepancies that the stories cannot stand. If Bloomberg cannot present credible information to show how the hack presented is possible, plausible, and did happen, Bloomberg needs to retract the story and investigate how this passed editorial muster and was published.

(Via 9to5Mac)